Difference between revisions of "History: The Great Mandrake"

Iceagefarmer (talk | contribs) |

Iceagefarmer (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

Normal or predictable spring and autumn flooding was increasingly replaced by large-area and intense flooding, sometimes outside spring and autumn from about 1300, in recurring crises which lasted into the 18th century. In the Low Countries and across Europe, but also elsewhere, the cooling trend starting in the late 13th century became more intense. It brought long cold winters, heavy storms and floods, loss of coastal farmlands, and huge summer sandstorms in coastal areas further damaging agriculture. Climate historians estimate that major flooding on an unpredictable but increasingly frequent basis started as early as 1250. Extreme events like the Grote Mandrake flood of 1362 which killed at least 100 000 people became darkly repetitive. | Normal or predictable spring and autumn flooding was increasingly replaced by large-area and intense flooding, sometimes outside spring and autumn from about 1300, in recurring crises which lasted into the 18th century. In the Low Countries and across Europe, but also elsewhere, the cooling trend starting in the late 13th century became more intense. It brought long cold winters, heavy storms and floods, loss of coastal farmlands, and huge summer sandstorms in coastal areas further damaging agriculture. Climate historians estimate that major flooding on an unpredictable but increasingly frequent basis started as early as 1250. Extreme events like the Grote Mandrake flood of 1362 which killed at least 100 000 people became darkly repetitive. | ||

| + | <youtube>pied0u2oP-Q</youtube> | ||

Other giant floods in the region through the next 200 years probably killed a total of 400 000 persons in the coastlands of what is now Belgium, Germany and Holland. At the time, Europe's population was at most a quarter of today's, meaning that corrected for population size these were really catastrophic disasters. During this time, the Zuider Zee region of northern Holland was inundated and its former farmlands disappeared under water – for several centuries. | Other giant floods in the region through the next 200 years probably killed a total of 400 000 persons in the coastlands of what is now Belgium, Germany and Holland. At the time, Europe's population was at most a quarter of today's, meaning that corrected for population size these were really catastrophic disasters. During this time, the Zuider Zee region of northern Holland was inundated and its former farmlands disappeared under water – for several centuries. | ||

Latest revision as of 00:57, 23 October 2018

THE GREAT DROWNING

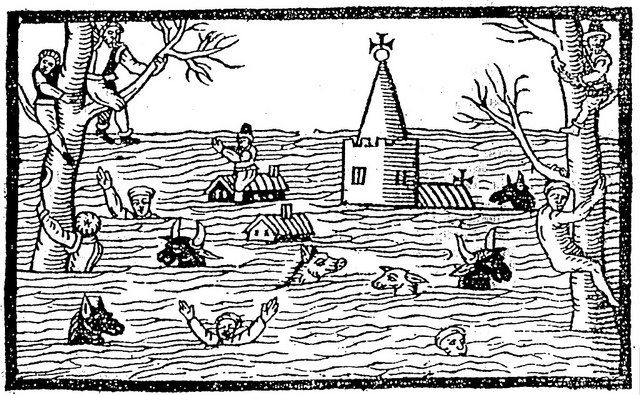

For the Dutch, the Grote Mandrake means “The Great Drowning” and is named for the epic and massive flooding that occurred, more and more frequently in the Low Countries of Europe's North Sea region as Europe's Little Ice Age intensified.

Normal or predictable spring and autumn flooding was increasingly replaced by large-area and intense flooding, sometimes outside spring and autumn from about 1300, in recurring crises which lasted into the 18th century. In the Low Countries and across Europe, but also elsewhere, the cooling trend starting in the late 13th century became more intense. It brought long cold winters, heavy storms and floods, loss of coastal farmlands, and huge summer sandstorms in coastal areas further damaging agriculture. Climate historians estimate that major flooding on an unpredictable but increasingly frequent basis started as early as 1250. Extreme events like the Grote Mandrake flood of 1362 which killed at least 100 000 people became darkly repetitive.

Other giant floods in the region through the next 200 years probably killed a total of 400 000 persons in the coastlands of what is now Belgium, Germany and Holland. At the time, Europe's population was at most a quarter of today's, meaning that corrected for population size these were really catastrophic disasters. During this time, the Zuider Zee region of northern Holland was inundated and its former farmlands disappeared under water – for several centuries.

The basic reasons was that the weather was getting colder, as well as more unpredictable. As the climate cooled, it also became wetter. Combined with the cold, this caused more crop failures and famines spread as the northern limit of farming retreated south. The start of the cooling – called Europe's Little Ice Age by glaciologist Francois Matthes in 1939 – in the 13th century was in fact the start of a long, sometimes steep dip in temperatures that held sway on an unpredictable, on-and-off basis until at least the first decade of the 19th century. Overall, the cooling lasted about 450 years.

Making things worse, the cooling had been preceded by more than two centuries of much warmer and better, more predictable weather. Farming moved northwards, seasons were predictable, food supplies had expanded. Europe's population also grew, in some regions tripling in 200 years. The colonization of Greenland, which failed when the cooling intensified, was a well-known historical spinoff from the previous warming, but by the 16th century there was no trace of Europeans in Greenland. Only ruins of their farms and homes could be found, but with few or no tombstones dated beyond the early 15th century, leading to the theory that these early “Climate Refugees” packed their longboats and sailed south, to what is now the New England coast. Where they became easy prey for American Indian tribes along those coasts.

ECONOMIC DISASTER By the 14th century the cooling had become an economic disaster in Europe as the northern limit of arable farming, and the altitude limit on farming, retreated southwards and downhill. Traces of ancient fields and farms, vineyards and pastureland in northern Europe, show this retreat. Failing food supplies quite rapidly caused or triggered armed invasion and war for control of remaining croplands. The 1315 Flanders campaign of Louis X who ruled large parts of today's France was an example. While 1315 was disastrous, the previous year had been almost as bad for farming output across much of Europe, due to persistent cold and torrential rains. Thousands of hectares of cereal crops were lost, and hay for feeding farm animals could not be stored and used, because of rot and mildew.

Constant gales and floods affected the North Sea coasts and to this backdrop, spurred by rivalry and conflict among Europe's constantly bickering royal families, Louis sought a military solution to the ongoing Flanders problem, caused by his disputes with a distant relative, the Count of Flanders. At the time, due to the previous Warm Period, Flanders had amassed considerable wealth including easier-stored agricultural wealth in the shape of its woolens, carpets, wine and timber. Flanders was an "immensely wealthy state", inciting Louis X to claim suzerainty over it, like his predecessor Philip IV whose army had been beaten back when he attempted to assert French control.

By 1315 the more basic issue of food supply set a short fuze to the situation. The attempt by Louis to “deliver a military solution”, mobilising a large army along the Flanders border with the promise of booty for the troops was risky – given the weather – but Louis had taken the gamble. Louis X prohibited exports of grain from France to Flanders, knowing their stocks of food were already low due to the ongoing bad weather, but Flanders beat the food blockade by using its wealth to buy imported food from Spain, the Baltic states and England. This food smuggling laid the basis for later rapid peacetime growth of food trade between north and south Europe – but also enabled the extremely rapid transmission of the Black Death bubonic plague epidemic, which peaked in 1348-1350 and probably killed at least 150 million people right across Europe.

In 1315, the Flanders campaign of King Louis was soon literally bogged down in the flooded chilly fields of Flanders. Louis was forced to use military requisition to feed his troops, resulting in a string of complaints from local lords and from the Church. As his losses mounted, and the weather remained very bad, Louis X was forced to abandon the campaign.

Directly but apparently unrelated, Louis X was also the first royal patron of 'jeu de paume', or indoor tennis, and ordered the construction of indoor tennis courts comparable to modern ones. His entourage of court followers had become unhappy playing tennis out of doors in the increasingly wet, windy and chilly summers of the early 14th century. Weather and royal patronage aiding, the new sheltered indoor tennis sport spread through Europe's royal palaces, but Louis X himself paid a high price. In June 1316 at his Val-de-Marne chateau, following a strenuous game of indoor tennis he went outside to drink wine on an already typically overcast, cool and wet summer evening - and subsequently died of either pneumonia or pleurisy.

THE COOLING CONTINUED To be sure, the major ideological or political problem with accepting firstly a two or three century period of warming, followed by a long period of cooling in the northern hemisphere and very widespread – from northern Latin America to China, North America and Europe – is that any possible linkage with human carbon dioxide emissions can be instantly discarded.

One argument used by leading lights of the IPCC such as Michael 'Hockey Stick' Mann is the claim that the Little Ice Age was not a “globally synchronous cold period”, but only a large-scale climate event marked by no more than modest cooling in most of the areas it affected on a variable basis, through the period claimed by the IPCC as about 1600-1800.

As we know, unpredictable and generally much colder weather is well known and historically documented in Europe starting in the 14th century.

The key factor of lowered weather predictability, and especially the increase in year-round rainfall and rainstorms – or “weather disruption” - were themselves enough to cause major economic and human losses. The climate historian Hubert H. Lamb in his 2002 book 'Climate History and the Modern World' dates the cooling to two main phases. The first leg of this change he places at about 1200-1400, but his second phase of about 1500-1825 which for some climate historians is Europe's Little Ice Age, was marked by much steeper drops in average temperatures. Indicators used by Lamb and other climate historians like Emmanuel Leroy Ladrie and Wolfgang Behringer include food price peaks as cold summers followed cold and wet springs, with increasing examples of “climate wars”, such as Louis X's Flanders campaign where the climate chilling was a sure factor in play.

One social group in particular suffered from Europe's deterioriating weather conditions - people thought to be witches. Wolfgang Behringer details the rapid increase in witch hunts across Europe – and then in the newly founded USA – because weather-making was thought to be the traditional purview of witches. In Europe, from the late fourteenth century and for at least a century, what can be called the Great Witch Conspiracy emerged. Witch hunts were always most intensive and cruel during the most severe years of the cooling as people looked for scapegoats to blame for their suffering.

As the cold winds from the north intensified and the polar jet stream strengthened, the frequency of storms mounted. Massive winter and springtime flooding became all too commonplace in the 14th century – but were set to re-intensify in later centuries. Sea levels had likely increased through ice melt during the previous two-to-three century warming, which compounded the flood damage. The greatest North Sea floods of the cooling period after the Grote Mandrake, in 1421, 1446 and 1570, probably killed a total of 400 000 persons in affected coastal regions, but the sharpened cooling had many other disastrous effects. Farms and their croplands which had survived the cold, wet and long winter were on frequent occasions later hit by summertime hail, floods, wind and sandstorms, killing livestock and destroying crops, as very cold and warm air masses collided. Farming in coastal areas, apart from the flooding, was also damaged by severe erosion due to continual high winds and storm surges leading to salination and frequent sand storms “so huge they could only be due to witches”

Today's IPCC climatologists, who only pursue a “warmist” agenda, can of course brush aside the length, intensity and damage caused by Europe's Little Ice Age but the fact of weather variability radically increasing, in Europe during that period, cannot be denied. One of history's most notorious quotes may have been caused by an unfortunately typical effect of this weather disruption. Northern France, after an all-too-usual bad winter in 1787-88, experienced extreme heat in May and June – destroying a large amount of the grain crops which had survived the previous cold. On July 13, at harvest time, a massive hailstorm caused by the mixing of very cold and warm air masses destroyed what little crops remained. The bad harvest of 1788 was followed by the bread riots of 1789. In front of the Bastille prison in Paris, the rioters became ever more dangerous, prompting Marie Antoinette's famous one-liner: "Let them eat cake", because, as she knew, they had no bread.

BEWARE OF COOLING As we know, a major morph of global warming theory, and the way it is now promoted in media, political and corporate agendas, is that anthropogenic weather disruption due to CO2 or “carbon effluent in the atmosphere” is the new major fear, replacing global warming fear. The lack of any scientifically proven and provable global warming since 1998, despite rising CO2 levels, is a good explanation of why this “new official crisis” has jumped off Barack Obama's teleprompter.

So far and to date however, global cooling is strictly excluded as even remotely possible. This flies in the face of world climate history, where the changeover from warming, to cooling, was rapid and at least as important, was impossible to predict. To be sure we have vastly better scientific methods and equipment available today, but the ideological basis of global warming theory – and its present mutant of “anthropogenic weather disruption” - does not allow for the possibility of cooling. Simply due to global cooling being “permanently off limits”, cooling remains a constant possibility and threat.

Global cooling began at the end of the so-called Medieval Warm Period, by or before the year 1300, and was preceded by at least 200 years, and as long as 350 years, of warming on the same variable and unpredictable basis. Measurement problems include the type of proxies used – ice cores, tree rings, corals and shells, others – but at least as important, the ideological bias of climate science leads to extreme variations in reconstructed climate data for the same region, same period. One flagrant example is IPCC treatment of Medieval Warming Period data – as published by the IPCC in different editions of its reports and studies. Before year 2000, IPCC studies include papers showing Warm Period temperatures in certain high latitude locations at certain dates around 950-1200 as several full degrees celsius above present day temperatures.

That is, despiter 213 years of anthropogenic global warming if with the IPCC we use a start date of 1800 for human “carbon pollution of the atmosphere”, we have in no way matched this natural warming. Which needed zero assistance from human-source CO2.

Other major problems also exist. Equatorial and low latitude regional climate change has always been the “poor cousin” of political, media and corporate interest in the subject, obscuring the fact that while higher latitude regions were general losers from global cooling – low latitude regions were winners. While peak temperatures on a short term base in these regions through 30 degN-30 degS were possibly or probably not significantly different from today, this ignores the major beneficial weather change – in these regions – caused by cooling. Conversely, further away from the Equator, the intensity of cooling and peak lows of temperature experienced after the end of the Warm Period, were impressive.

Since 1800 using the best-highest claims of the IPCC, world average temperatures have risen by at most 1 degC. During the Warm Period before year 1300, in some high latitude regions, temperatures were probably at least 5 degC higher than afterwards, during the Little ice Age, and 4 degC higher than today. The recovery since the Little Ice Age would in theory have a long way to go – assuming it can go that far. Assuming it can't, and the Earth's climate clock may not allow the time, temperature falls of at least 1.5 degC are logical and totally possible. Just as important, the cooling can be rapid and will be accompanied by much wetter, unpredictable and “unseasonable” weather.

This is the global cooling fear.